- Home

- Sarah McBride

Tomorrow Will Be Different Page 2

Tomorrow Will Be Different Read online

Page 2

One in four transgender people in the report had been fired from their job because they were transgender.

One in five had been homeless.

And 41 percent had attempted suicide at some point in their lives. Nearly half had tried to end their lives, in many cases because the world was too hateful to bear.

Still, after two decades, I knew that nothing—not even my biggest dreams—would make the pain worth it. Now, sitting there, my hand on my mouse, I took a deep breath and posted the message.

The die was cast and there was nothing more I could do about it. My secret was out there.

It didn’t take long for the news to spread like wildfire. Comments came flooding in, not just from my friends but also from classmates whom I barely knew. Miraculously, every single one of the messages was full of love and support.

One student commented, “If you ever begin to feel that your ambitions and determination to live openly as yourself cannot coexist, please remember this moment. This is leadership. I’ve never been more proud to have you as our president.”

Another student wrote, “This is one of those times when I’m incredibly proud to go to AU and be a part of such an accepting community. The world just became a bit more tolerant and a bit more open today with your help.”

“AU takes Pride in McBride,” a classmate posted.

I leaned back in my chair, overcome with the relief at the responses. They were nothing like I had feared. A weight had lifted from my shoulders. I was out and the world had not collapsed. Fear of the unknown no longer stood in the way of completeness. I felt free.

My amazement was interrupted by three knocks on the door. I wiped the tears that had begun to fill my eyes, walked over, and opened the large glass door that led into the executive suite. Standing in the hall was a line of seven men, most of them wearing shirts stamped with a jumble of Greek letters.

They were my fraternity brothers. I had joined a year earlier after some pressure from a few friends and one last-ditch attempt at trying to prove to myself that I was someone I knew I wasn’t.

The brothers outstretched their arms and, one by one, stepped up to give me a hug. They knew I had just amicably disaffiliated for obvious reasons and they wanted to make clear, in person, that they were still there for me. That I may not be their fraternity brother anymore, but that I’d always be their sister.

As they left, the editor of the school newspaper, The Eagle, made his way to my office. Zach, an AU sophomore with a full dark beard, thick head of hair, and wire-rimmed glasses, looked the part of an aspiring newspaper editor. He had just taken over the paper for the coming year and he came with a question and a request.

“We have several pieces in tomorrow’s paper that reference you and your time in office. Would you like us to change your name and pronouns in the pieces to reflect your note?” he asked.

“Absolutely,” I responded, thankful for his thoughtfulness in his approach to my news and his new job.

He cleared his throat for the next question. It was clear he was worried it would be invasive or inappropriate.

“Would you be interested in publishing your coming-out note in tomorrow’s paper?”

I had actually thought about asking The Eagle to publish my note but almost immediately dismissed it as a self-indulgent exercise. But when Zach asked, I thought: Maybe this isn’t actually self-indulgent. Maybe this is an opportunity to educate. Maybe my journey, as limited as it is, deserves to be heard. I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to humanize trans identities—to humanize myself—for whoever would read my piece. I hoped that perhaps my words could provide an entry point for my peers and maybe even a few strangers to tap into the most powerful human emotion: empathy.

“I think that would be great, yes,” I responded.

“Great. That’s great. One thing, though…” He hesitated for a moment. “It’s a little long. We’d need to cut it down to around six hundred words.”

We made our way down the hall toward the student newspaper offices so I could work with him to cut my twelve-hundred-word announcement in half. When I walked into the bustling, cramped, on-deadline, and completely filled newsroom, the space fell silent. I had just walked into a room where everyone had clearly been talking about me. I worried that this awkward moment would represent the rest of my life. Or, at least, for the year that I had left at AU.

I walked through the open space and into a small room with a single computer in the back. I sat there with Zach, cutting and adjusting. Each word, each thought, felt critically important, but column inches supersede all.

An hour later, we had whittled it down to just about six hundred words. By now my phone had started to blow up with texts, calls, and emails, many from the media outside of AU. I prepared to walk into the newsroom again.

As I opened the door, a hush fell back over the room. But this time, the atmosphere felt different. Everyone was smiling. And not in the “we’re laughing at you” kind of way that I’d feared. Their smiles contained a sense of pride. A simple look of “good job” coupled with a nod. A few even stood up from their desks and shook my hand.

I had spent the previous year telling AU students, who were often more interested in interning on Capitol Hill than in improving their own campus, that they should not ignore the opportunities for change right in front of them. I told them that our campus should reflect the world we want to build in ten or fifteen years. After all, we were a student body uniquely skilled in political change, and we should invest some of our talents in our campus. I’d ask them, “If we cannot change our college, then how can we expect to change our country?”

And in the hours after posting my note on Facebook—and with the newspaper preparing to publish my piece—you could feel the buzz on campus. My post was already being shared throughout campus and beyond. And it was being met not with jokes and mockery but instead with celebration and excitement. That night, one student commented that the reaction from the student body to my news was like “we had won a sports championship.” A total and overwhelming outpouring of love and joy.

As the news spread beyond our campus, American University was readying to make a statement to the country: that while we may just be starting to learn about transgender identities, this is how you react—with love, kindness, and dignity. And that through AU’s example, this is the world we will help build.

Together, on that night, it felt like our campus was sending a small but powerful message: that for transgender people, tomorrow can be different.

It doesn’t always get better. Sometimes it is a step back; it’s the loss of a life, an act of hate, or the rescinding of rights in states like North Carolina and in the military. It’s the perpetuation of a status quo in which a majority of states and the federal government still lack clear protections from discrimination for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people; where too many remain at risk of being fired from their job, denied housing, or kicked out of a restaurant simply because of who they are.

But increasingly, it’s a step forward. The growing ranks of allies around the country; the cities and states that are stepping up to protect their LGBTQ residents from discrimination and violence; the increasing power of our voices that are, collectively, enacting change in homes and in schools, in city halls, and in the halls of Congress.

When I came out, I never anticipated just how far the LGBTQ community and movement would come in so short a time. Inheriting a legacy of advocates, activists, and everyday people who, through the flames of violence and the ashes of hatred, toiled and fought for a different world, we’ve grown into one of the most effective movements for social justice in history. And even as we’ve faced some crushing defeats, transgender people—and all LGBTQ individuals—have made historic advancements.

I’ve seen this progress firsthand in my own life and my own work. I saw it while fighting for equality in my home st

ate of Delaware and in the transforming love of a husband who helped make my life possible even while he was losing his own. I saw it onstage at the Democratic National Convention and I continue to see it every day traveling around the country to stand with a community that is finally being seen and affirmed in our beauty and authenticity.

After a decade of unprecedented progress, the knowledge that change is possible, the hope of a better day, is the fuel that drives us. We strive toward a world where every person can live their life to the fullest. While the progress is uneven and can come in fits and starts, I still know today—years after that night at American University—that, with hard work and compassion, we can make more tomorrows better than today.

CHAPTER 1

“I’m transgender.”

Growing up, the TV was always on in my house.

So it was fitting that the first time I heard the word “transgender,” I was ten years old and watching television.

The den on the second floor of our home was totally dark except for the light from Just Shoot Me!, a weekly television show about a women’s fashion magazine, when a guest character named Brandi—played by the beautiful Jenny McCarthy—appeared on the screen. Brandi had been the best friend of one of the show’s main characters, played by David Spade, in elementary school. But the story came with a twist: Spade had known Brandi only as a boy, but now here she was, a beautiful woman.

Cue the laugh track.

I turned to my mom, a warm and friendly woman around the age of fifty at the time, who was sitting across from me in a recliner. I gulped and asked her, “Can people really change their gender?”

I worried that even asking the question would raise questions about me. In the moments since Brandi’s twist was revealed, I had quickly convinced myself that this was a possibility that existed only in the world of television.

My mom responded nonchalantly, still focused on the show. “Yes, they’re called transgender. Or something like that.”

Oh my God, that’s me, I thought. The show wasn’t particularly disrespectful by the standards of late-1990s/early-2000s television, but the joke was clearly that Brandi, a transgender woman, was of even passing interest to other human beings. It was hilarious that people were attracted to her. The audience’s laughter built up every time someone commented on her looks, not knowing that she was really trans.

Representation in popular culture is key. It is often the first way many of us learn about different identities, cultures, and ideas. That evening’s episode had offered me the life-affirming revelation that there are other people like me and that there was a way for me to live my truth. But it did so in a way that made clear that, should I take that path, I’d be risking pretty much everything, from finding someone who would love me as me to being taken seriously by the broader world.

Ten-year-olds don’t know a lot, but they know that they don’t want to be a joke. Looking at my mom, that realization sank in. I’m going to have to tell her this someday, and she is going to be so disappointed.

Watching this sitcom wasn’t the beginning of this struggle for me. For as long as I can remember, I’ve known who I am. For the first ten years of my life, I didn’t know there was anything I could do about it or that there were other people like me, but I knew who I was. It wasn’t that I knew I was different. I knew, specifically, that I was a girl.

When the boys and girls would line up separately in kindergarten, I’d find myself longing to be in the other line. The rigid and binary gender lines are made abundantly clear to all of us at a young age, from the color-coded clothing to “boy’s toys” and “girl’s toys.” For a five-year-old, the distance between the two gendered lines in kindergarten might as well be a mile apart. It was clear: There was no crossing of the divide, under any circumstances.

* * *

I grew up on a picturesque block of large homes in west Wilmington, Delaware, a beautiful tree-lined street of three-story, symmetrical houses built in the 1920s. The neighborhood was filled with young families of lawyers, doctors, and accountants. The kids, all roughly my age, would meet every night for a game of tag or capture the flag. While it was the 1990s, the atmosphere could have been the 1950s. It could have been Leave It to Beaver.

Just across the street from us was the home of two girls, Courtney and Stephanie, a year younger and a year older than me. Their house became my escape. In the playroom, located away from all the parents, they’d let me put on their different Disney princess dresses. My favorite was a shiny blue Cinderella dress. Putting it on and looking down, I felt the longing go away. A completeness instantly came over me, and a dull pain that I didn’t fully understand was gone.

But every time, as I’d play in the Cinderella dress, the proverbial stroke of midnight would arrive. I’d have to take it off and return to playing the part that I’d already learned was more than just expected of me—it was “me” to everyone else in my life. I was playing an extended game of dress-up, a part society had thrust on me that, it seemed, I had no choice but to follow.

All of this was four or five years before I saw that sitcom with my mom. Convinced that there was no way out, I’d dream of the universe intervening. I’d lie in bed each night and pray that I’d wake up the next day and be myself, for my closet to be filled with dresses, and for my family to still love me and be proud of me.

By the time I had “officially” learned about transgender people at the age of ten, I’d already grown a deep interest in politics. As a young kid, I loved building blocks and constructing elaborate houses out of them. By six, I’d spend nights and weekends building detailed re-creations of the White House in my bedroom. Nerdy, I know.

The first books I started to read were, naturally, about the building and the history within it. Soon, I was voraciously reading about the presidents and gaining a profound love of history. In elementary school, my teachers and other parents had already started calling me “the little president.”

Me, my endless smile, and the best blue-blazer imitation suit jacket a seven-year-old could muster.

As a young person first gaining a fuller perspective on the size of the world, the scope of the social change I read about fascinated me. I devoured books about Franklin Roosevelt, his New Deal, and World War II. I became obsessed with Lincoln.

But nothing inspired me more than the fights for equal rights at the center of our history. Each generation, it became clear, was defined by whether they expanded equality, welcoming and including people who had once been excluded or rejected.

And as I began to understand that there was something about me that society disapproved of, I became drawn not just to the history, but also to the possibility of politics as a means of fixing society. Of creating a world that was a little more loving and inclusive. Even if I couldn’t fix it for myself, I thought that fixing it for others could make my life worthwhile.

Being me appeared so impossible that changing the world seemed like the more realistic bet. And the thought of doing both at the same time was, in a word, incomprehensible. Something became abundantly clear to me as I read my history books: No one like me had ever made it very far. Or, at least, no one who had come out and lived their truth.

At an early age, I was very aware of just how lucky I was. As we drove across town to my elementary school, the privilege that my family enjoyed was clear. I knew just how fortunate I was to have the opportunities that I did, but I still felt alone. And more than anything else, I felt resigned to a life that required me to choose between who I am and the kind of life I hoped for.

Politics seemed, comparatively, so attainable and tangible. Growing up, I personally knew more U.S. senators than transgender people. With Delaware as small as it is, a state of less than a million people, we’d routinely see our elected officials at the grocery store or the gym. And to any young person remotely interested in politics in Delaware in the

early 2000s, one man stood above the rest. At eleven years old, I met my political idol.

Joe Biden was a towering figure to me. Even before he was selected as Barack Obama’s running mate, he was the hometown kid who had made it big, the Delawarean who had become a national figure with presidential ambition and buzz. When I first met him at a local pizza shop while eating with my parents, I was star-struck. Here was the guy I had seen on the news—right in front of me.

He had just gotten off the Amtrak from D.C. and was meeting his wife, Jill, for dinner. They sat right next to our table. And knowing how much it would mean to me, my parents introduced me as he walked over.

I was speechless. I just stared up at him, barely able to introduce myself.

He kneeled down, ripped out his schedule for the day from his briefing book, and pulled out a pen.

“Remember me when you are president,” he wrote, followed by his signature.

I stared at the page for the remainder of dinner and, when we got home that night, promptly hung it in my bedroom next to my Little League trophies. The February 1, 2002, Joe Biden schedule became my prized possession as a kid.

And in early 2004 I got my first real taste of Delaware politics. My dad, a compassionate, intellectually curious, and hardworking attorney, told me that his colleague Matt Denn had decided to run for insurance commissioner, a statewide position charged with overseeing the insurance industry in Delaware that, for some reason, is elected in our state.

Perhaps doing my father a favor because he knew how much I loved politics, Matt graciously allowed me and my friends, some of whom were equally interested in politics, to travel around with him as he campaigned. Most of the time, we’d hand out campaign literature or make phone calls on his behalf, but since we had started developing a strong interest in film as well, we also trailed the candidate with a big video camera for a documentary on his race.

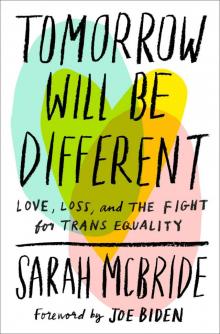

Tomorrow Will Be Different

Tomorrow Will Be Different